Meow (ops…hello!) to all, intrepid explorers!

I’m sure you all know about jellyfish, but I’d bet a whisker that there is someone among you who hasn’t heard of the “immortal jellyfish” yet.

Well: ypu know that I don’t like to leave anyone behind, so let me briefly introduce the topic, giving you some information about what a jellyfish is scientifically. I apologize in advance if I will use terms that may seem difficult to understand, but they concern scientific names that cannot be omitted in the description. If you need more information, you can read up on the encyclopedia, on any other book or website you prefer.

Jellyfishes belong to the phylum (definition used for the classification of living beings which generally indicates the type to which an animal belongs) of the Cnidarians. Cnidarians, also known as Coelenterates, are animals that possess a radial symmetry and live in water. It’s interesting to know that the term “Cnidarians” derives from the Greek word knídē, which literally means ‘nettle’, a name that fully captures one of the best known characteristics of these living beings, namely the fact that they are highly stinging.

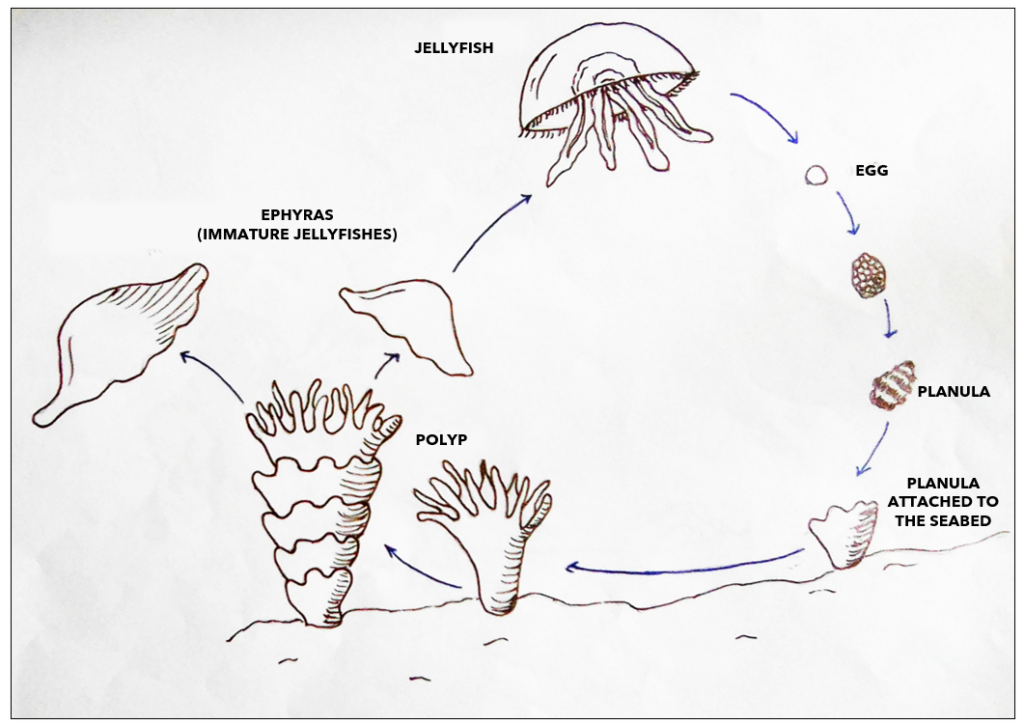

A jellyfish develops from a polyp, which lives in colonies anchored on the seabed. Reached maturity, it can generate both other polyps and jellyfish. In detail:

– through a process defined as “gemmation”, the polyp generates other polyps. Generally, they stick to the polyp that gave them birth and increase the size of the colony on the seabed. However, in some cases the polyps can detach from the bottom and live an independent life;

– particular polyps, called gonophores, have the ability to generate jellyfish, which can conceive other polyps through reproduction.

Here is my drawing that schematizes this particular life cycle.

Although apparently very different from each other, the polyp and the jellyfish have similarities. In fact, as generally happens for all Cnidarians, both the body of the polyp and that of the jellyfish have only one opening, surrounded by tentacles. Although it may seem strange, this acts as a passage that allows both to feed and to expel unwanted substances and carbon dioxide. The interior of the body, the so-called celenteron, has the task of digesting food and conveying water to all the cells of the animal, allowing the supply of nutrients and the exchange of oxygen and the expulsion of carbon dioxide or other waste substances.

Of course, there are also important differences between the two vital stages (polyp/ jellyfish) of this animal, which can be essentially summarized in these characteristics:

– shape: the polyp’s tentacles are oriented upwards, while those of the jellyfish are facing downwards, as well as their mouth;

– movement: the polyp is anchored to the seabed, without the possibility of movement, while the jellyfish is free to move;

– the jellyfish is a singular being, in the sense that it doesn’t live in colonies like the polyp.

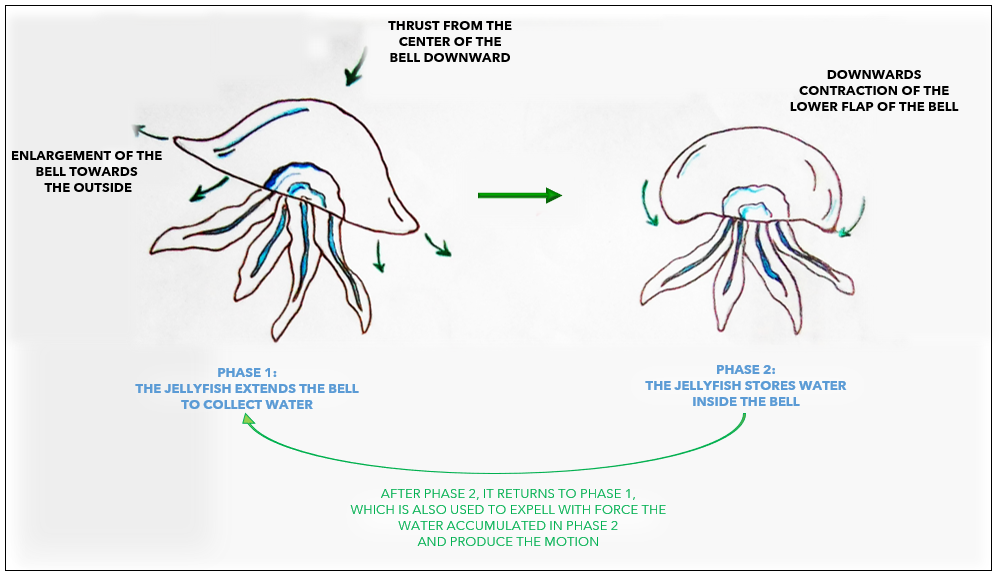

Jellyfish typically have the shape of a dome, or an umbrella if you prefer, with the concavity facing down. This part can be divided into an external upper (exombrella) and an internal lower (subumbrella). The internal “layer” between the esombrella and the subumbrella, with a gelatinous consistency, has a considerable thickness and acts as a support for the whole body. It is called “mesoglea”. Along the lower edge of the dome are the tentacles, in which the stinging cells are located.

Jellyfish have a planktonic behavior and follow the sea currents, within which they move with a mechanism that we could define as “jet swim”. In fact, they rhythmically contract the body, storing water inside it and then forcefully expelling it, which causes them to acquire a sort of jerky walk.

Here is my sketch of the “propulsion method” of this animal.

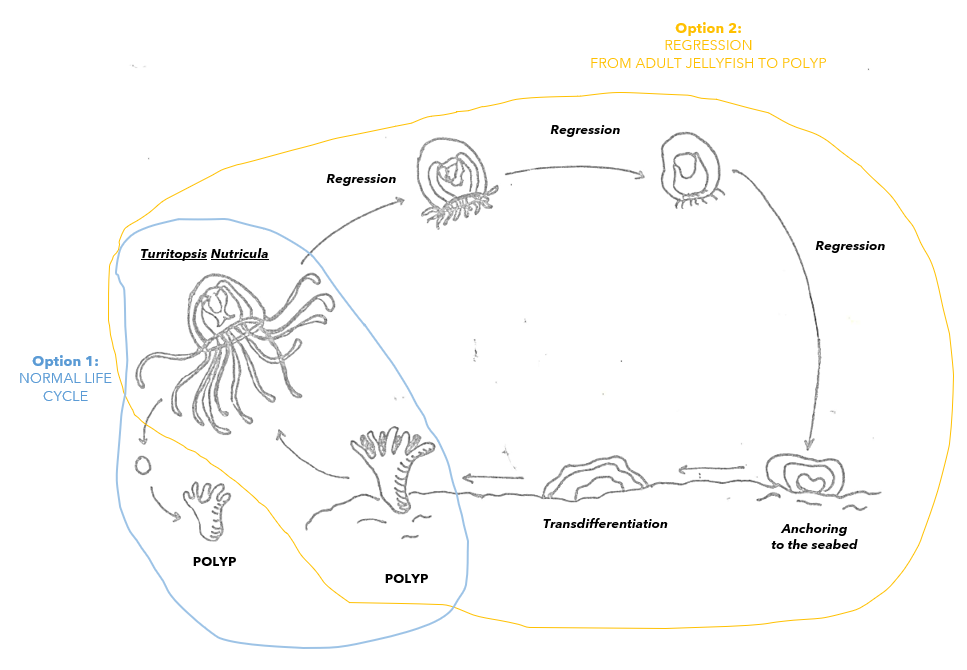

The immortal jellyfish, whose scientific name is “Turritopsis nutricula”, has the particularity of being able to return to the polyp state following the achievement of the adult stage and, according to what is currently known, remains the only animal species capable of implement this inversion of the life cycle.

In adulthood, it has the shape that I have drawn in the image below and its “dome” is no larger than about 4 mm – 5 mm in diameter. At the octopus stage, it has about ten tentacles, but when it becomes a jellyfish it can even have more than 80.

The life cycle of an immortal jellyfish generally follows that of a normal jellyfish, so it starts from the polyp stage, which lives on the seabed in colonies, and then moves on to the adult stage of jellyfish, a singular organism. In the common jellyfish, the adult stage is able to generate other polyps, but not to re-transform its organism into a polyp, reversing the life cycle, as happens for the Turritopsis Nutricula.

I draw a diagram that illustrates this curious life cycle.

Scientists dealing with this argument explain this ability with a phenomenon defined as “transdifferentiation”. This is a really complex concept, which I will try to summarize in a very simplified way, saying that it is a change due to the fact that cells already highly specialized in particular functions return to a non-specialized young phase.

It is this ability that has earned this animal the definition of “immortal”, because the cycle repeats itself an indefinite number of times which, potentially, could even become infinite (although at today this is still under study).

In reality, this process is also partially present in animals such as lizards, which use it, however, only to regenerate some parts of the body and not to start their life cycle all over again. If I may allow myself a brief unscientific parenthesis, I believe that the contribution of cats has been fundamental in the development of these abilities in lizards, since we love to chase them. And if that rascal tail didn’t always come off … how many would I have caught!

Anyway, let’s get serious. This is what I wanted to let you know today… wonderful the world, isn’t it?

If you think like me, don’t miss the next cat-astic curiosity from the world… and more!

You can also report unusual topics that you want to learn more, or questions, at the usual address: infopurr@astroartu.studio.